The grid has been a recurring theme in art for over a century, from the geometric abstractions of De Stijl to the minimalist canvases of the 1960s and 70s. Today, it underpins design, architecture, and digital interfaces alike. It offers structure, precision, and infinite possibility, but also a tension between control and creativity. Dutch minimalist artist Erris Huigens, who works under the name Deconstructie, explores this tension in his practice. What happens when order meets chaos?

On the floor of Erris Huigens’ studio in a former brick factory on the river Rijn lie stacks of books about artists such as Richard Serra and Donald Judd, as well as the Dutch movement De Stijl. Founded in 1917, this movement was characterised by abstraction, geometry, and the use of primary colours. Building upon the principles of De Stijl, the Minimalist art movement emerged in the 1960s and 70s and was characterised by the idea of reduction. Leading artists such as Richard Serra, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris returned to art’s essentials with as little mediation from the artist as possible.

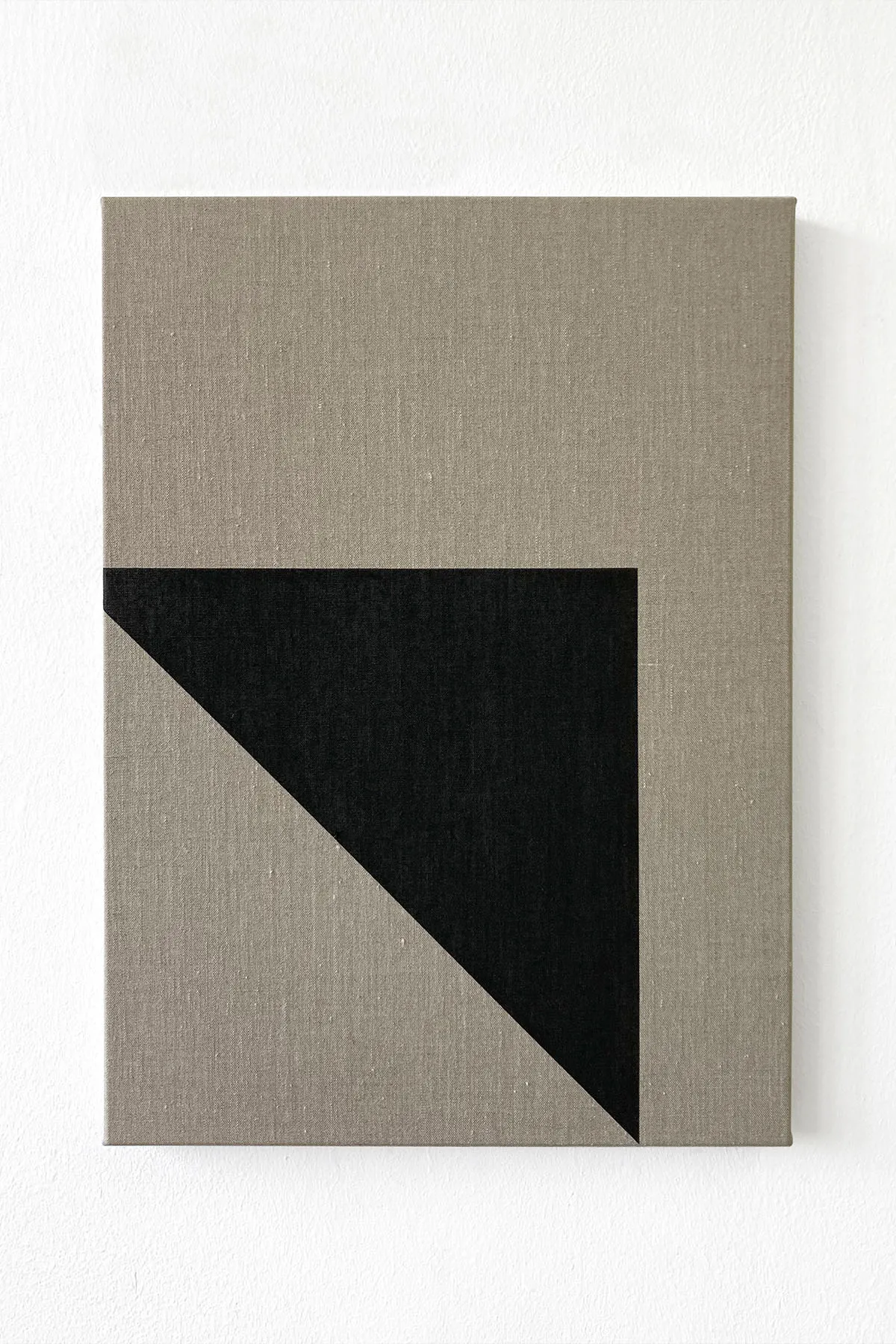

It’s not far-fetched to draw a parallel with these minimalists and the Dutch artist Erris Huigens, who presents his work under the name Deconstructie. In his exploration of geometry, he paints rectangular monochrome shapes in black and white, with missing corners, omitted parts – all measured with the utmost precision. He works on canvas, but his signature pieces are site-specific spray-painted paintings on the walls of vacant, dilapidated buildings at industrial sites. Without permission, sometimes disguised in a yellow work vest and well equipped with rulers, pencils, spray paint, paint rollers and chalk lines, he sneaks into these fenced properties – a technique executed with dexterity after years of spraying abstract graffiti in Leeuwarden, where he studied Art and Design. ‘As a graffiti painter, you observe a lot’, he explains when we meet up in his studio. Nowadays, his minimal paintings are still a result of reading the buildings and thriving on his intuition. ‘I enjoy creating things that are as minimal as possible, yet still meaningful.’

Huigens doesn't return empty-handed from these field trips. In the small attic of his studio in Wageningen, he stores a collection of stuff you’d rather expect in a shed: metal plates with holes, handles, some sort of Lego grid with small letters, rods and also a stack of Breuer tube chairs. Apart from the chairs, you could easily call it an attic full of trash with useless objects made out of steel, metal and wood – the treasury of a hoarder. But on closer inspection, these factory objects all seem to have a certain common denominator: grid-like plates with holes and patterns. Rows of steel panels with countless perforations, plates with Lego grids and some kind of bubble wrap – it’s a fascinating pattern-led collection.

'I enjoy creating things that are as minimal as possible, yet still meaningful'

The grid and the arts

The 21st century saw the rise of the grid as a subject of inquiry within the arts as modernity made its entrance in Western society. Ever since Russian constructivists like Kazimir Malevich used it as an emblem of socialist ideology, the grid has been a recurring tool, guideline and research theme of artists. Artists central to the De Stijl movement, such as Piet Mondriaan, Marlow Moss and Theo van Doesburg, picked up on the geometric shapes, and later it was employed by the minimalists of the 60s and 70s. But the grid travelled further into other domains. Graphic designer Josef Müller-Brockmann invented the celebrated grid system and describes its purpose as: “The grid is used by the typographer, graphic designer, photographer and exhibition designer for solving visual problems in two and three dimensions”. Architecture, (graphic) design and digital technology all adopted the grid – mostly as an organisational system.

But the grid brings many contradictions, which art critic Rosalind Krauss described in her grid theory in the late 70s. She thought the grid to be both material and spiritual: the grid can be a meaningless structural division of a canvas, but at the same time, it has a transcendental, timeless meaning that was emblematic of modernity at that time. The grid is both historical, with ties to the industrial revolution and modernity, and timeless. At the same time, the grid also provides both freedom and constriction – it’s guiding, but also limiting. How to navigate this balancing act?

Bending the grid

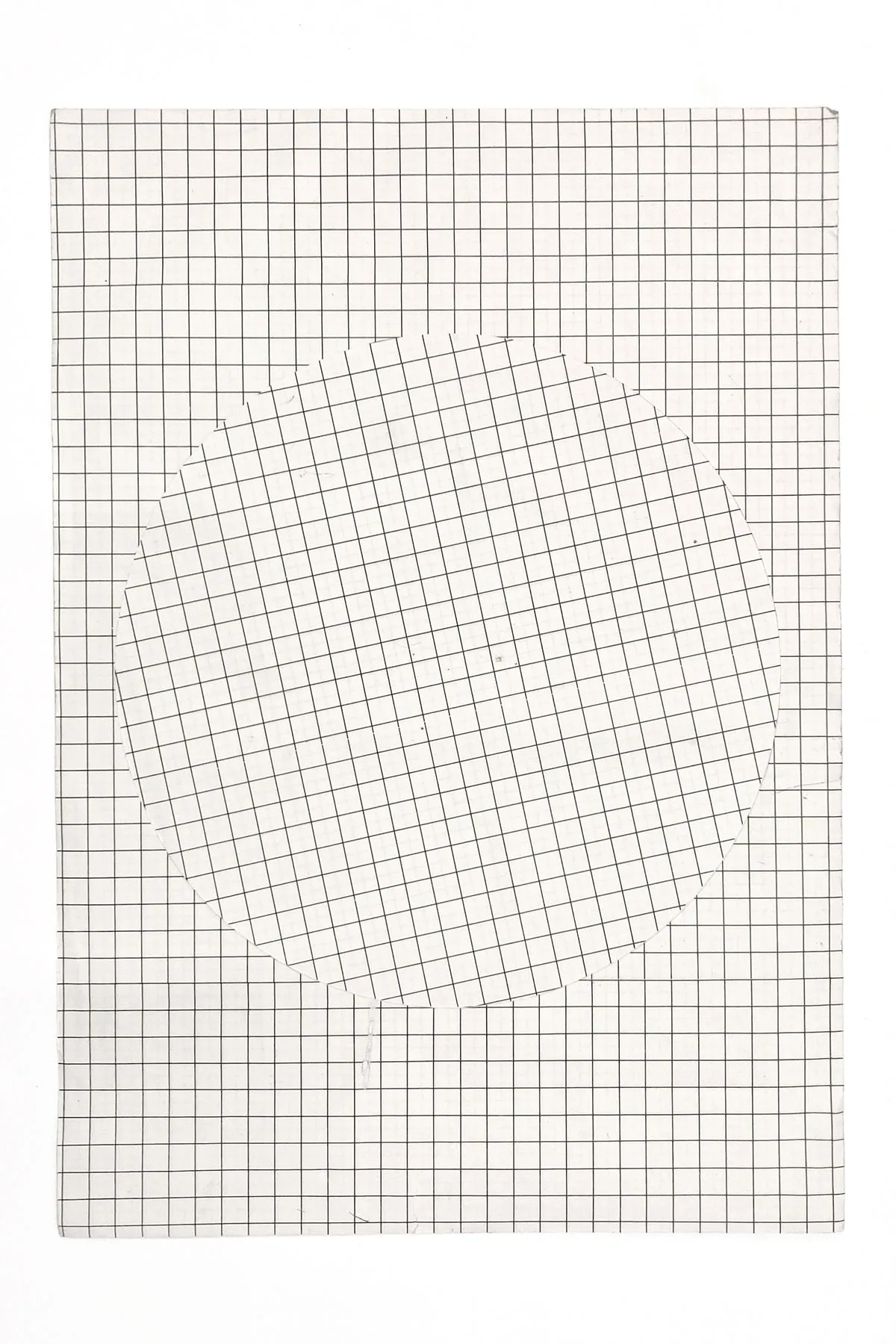

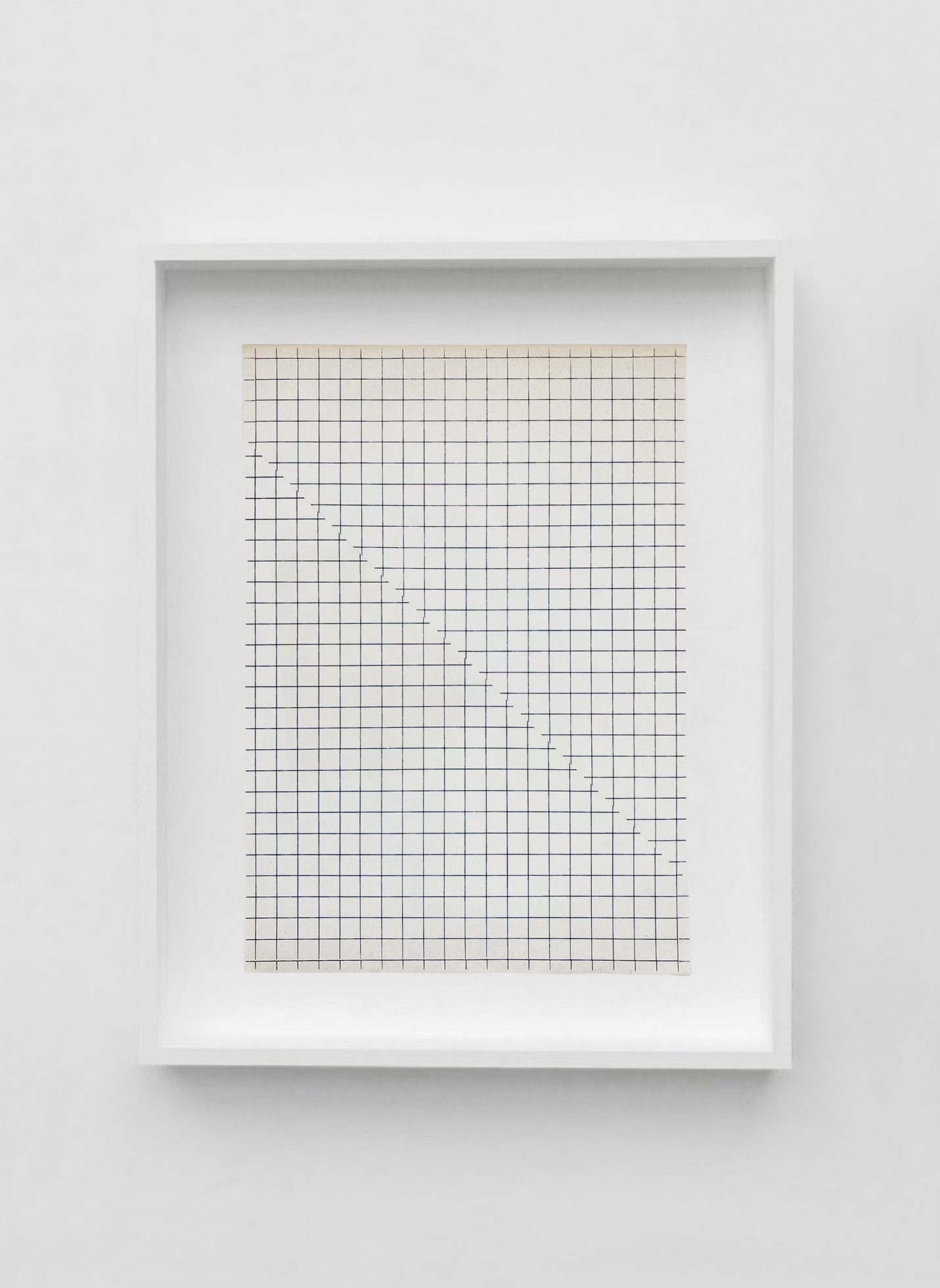

This tension of freedom and constriction is where we find Huigens’ art practice. Huigens’ paintings originate from his meticulous study of the grid. ‘It’s the starting point for a lot of the shapes that I make – I like to respond to something that already exists.’ Graph paper particularly fascinates him. ‘It’s a certain order that functions as my starting point, but that I also intend to break open. That’s why I came up with the name Deconstructie.’ Small explorations are his grid collages on paper, where he plays with disruptions of the grid by cutting the paper and connecting the pieces together in a way that the grid loses its structure, for instance, when he cuts out a circle and twists it a notch. It’s these choices in grid structure that make the grid a source of freedom.

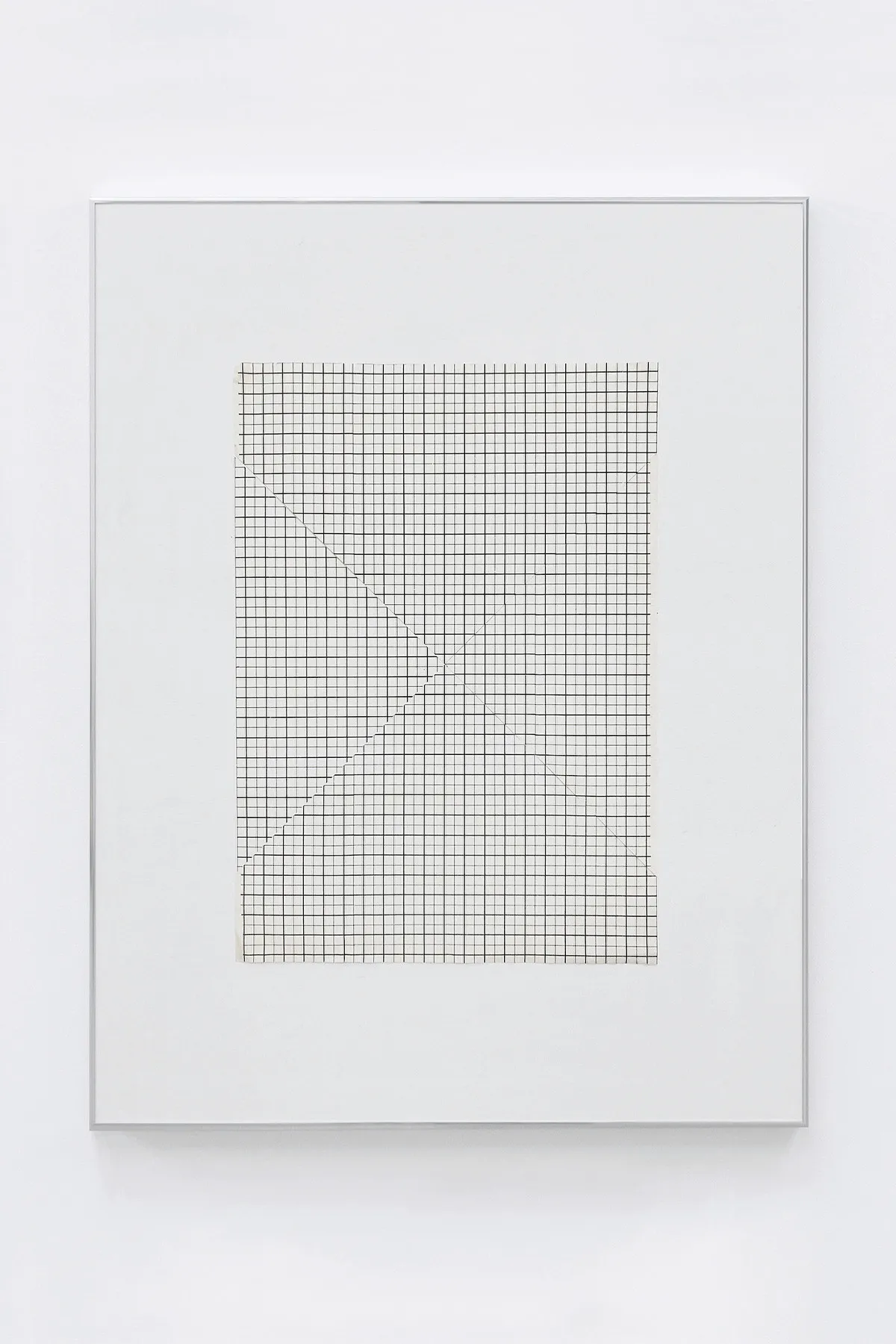

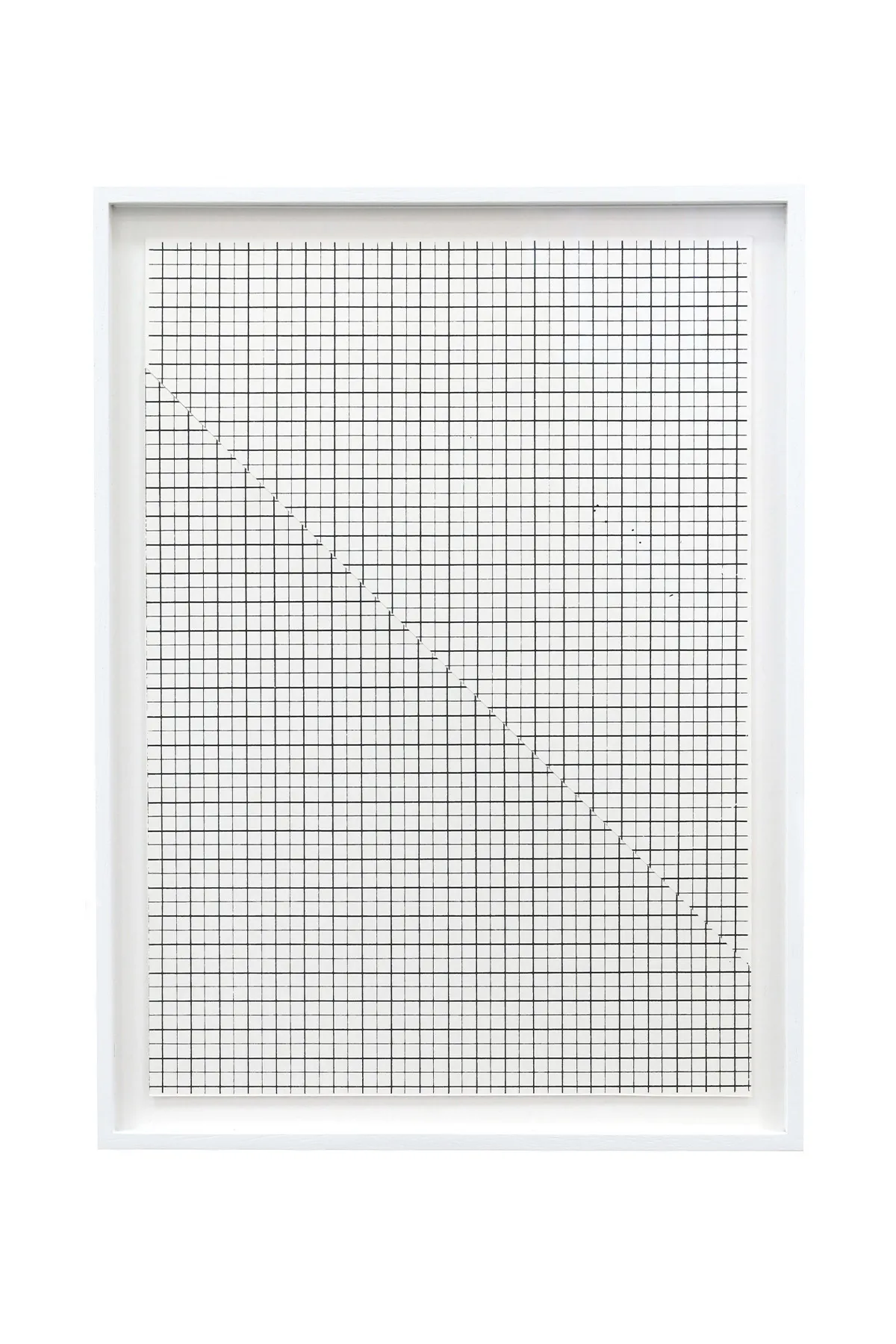

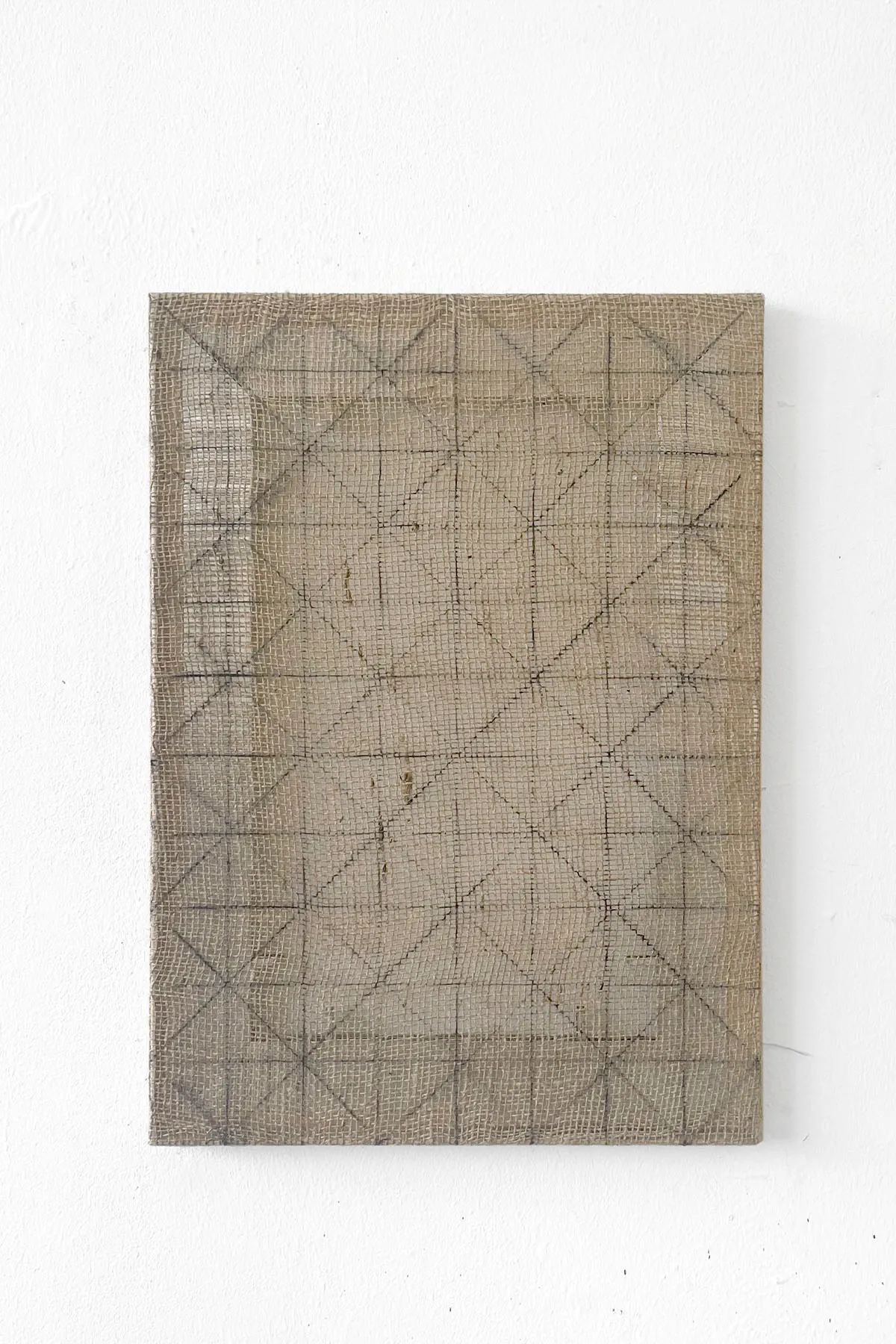

This break with grid order extends to his paintings. Inherently, a square or rectangular canvas can be seen as a grid particle (Huigens uses these as building blocks in works where he creates grids by combining different rectangular-shaped works or objects). In Huigens work, there is always a break with the order of this particle: a canvas with cut-out pieces, a ripped-out canvas, leaving just the metal frame bare, or a sketch-like, fragile-looking grid on a rough surface like jute. ‘A work can even be unfinished’, he affirms. Smaller gestures include the “broken” squares and rectangles he paints, as well as the positioning of paintings so that corners or doors break their 2D shapes.

Bending the grid

This tension of freedom and constriction is where we find Huigens’ art practice. Huigens’ paintings originate from his meticulous study of the grid. ‘It’s the starting point for a lot of the shapes that I make – I like to respond to something that already exists.’ Graph paper particularly fascinates him. ‘It’s a certain order that functions as my starting point, but that I also intend to break open. That’s why I came up with the name Deconstructie.’ Small explorations are his grid collages on paper, where he plays with disruptions of the grid by cutting the paper and connecting the pieces together in a way that the grid loses its structure, for instance, when he cuts out a circle and twists it a notch. It’s these choices in grid structure that make the grid a source of freedom.

This break with grid order extends to his paintings. Inherently, a square or rectangular canvas can be seen as a grid particle (Huigens uses these as building blocks in works where he creates grids by combining different rectangular-shaped works or objects). In Huigens work, there is always a break with the order of this particle: a canvas with cut-out pieces, a ripped-out canvas, leaving just the metal frame bare, or a sketch-like, fragile-looking grid on a rough surface like jute. ‘A work can even be unfinished’, he affirms. Smaller gestures include the “broken” squares and rectangles he paints, as well as the positioning of paintings so that corners or doors break their 2D shapes.

'In the end, it’s a constant play between order and breaking that order'

The factory as a living grid

The desolate sites Huigens visits for his site-specific work were once a functional grid – not only because of the intact brick-and-glass construction, but also because of the functionality of these old factories. With efficiency, these operated in optimal production modes, manufacturing whatever they were meant to produce. Now, dilapidated and often half collapsed, these are sites of inspiration for Huigens: ‘It’s raw, brutalistic, minimalist, industrial and functional.’

Roaming these places, Huigens stumbles across useless pieces that have fallen out of the grid. Once functional, these fragments are now useless, not existing for the sake of production - although Huigens sees that differently. While he adds paintings to the walls, he gathers these grid pieces for his studio collection. In his latest show at Proyecto REME gallery in Palma de Mallorca, we reunite with these pieces. They are showcased on the gallery floor, where the walls are robust, like the ruins from which these pieces were taken.

The minimalists of the 60’s were significantly involved with factory materials as they shifted from canvas to sculpture, believing that sculpture would communicate more directly than canvas, which was restricted by its flatness. In their avant-garde approach to art, they created space for the purity of industrial materials to escape any form of allusion. And so, Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Richard Long, and other minimalists, dragged stones, metal and pieces of wood into the exhibition space, without adornment.

But whilst these artists focused on the functionality and materiality of these objects, and eventually even moved to design art, Huigens exhibits them as they are. He embraces the roughness of these factory pieces, their inconsistencies and inefficiencies.

The grid as a binding force between disciplines

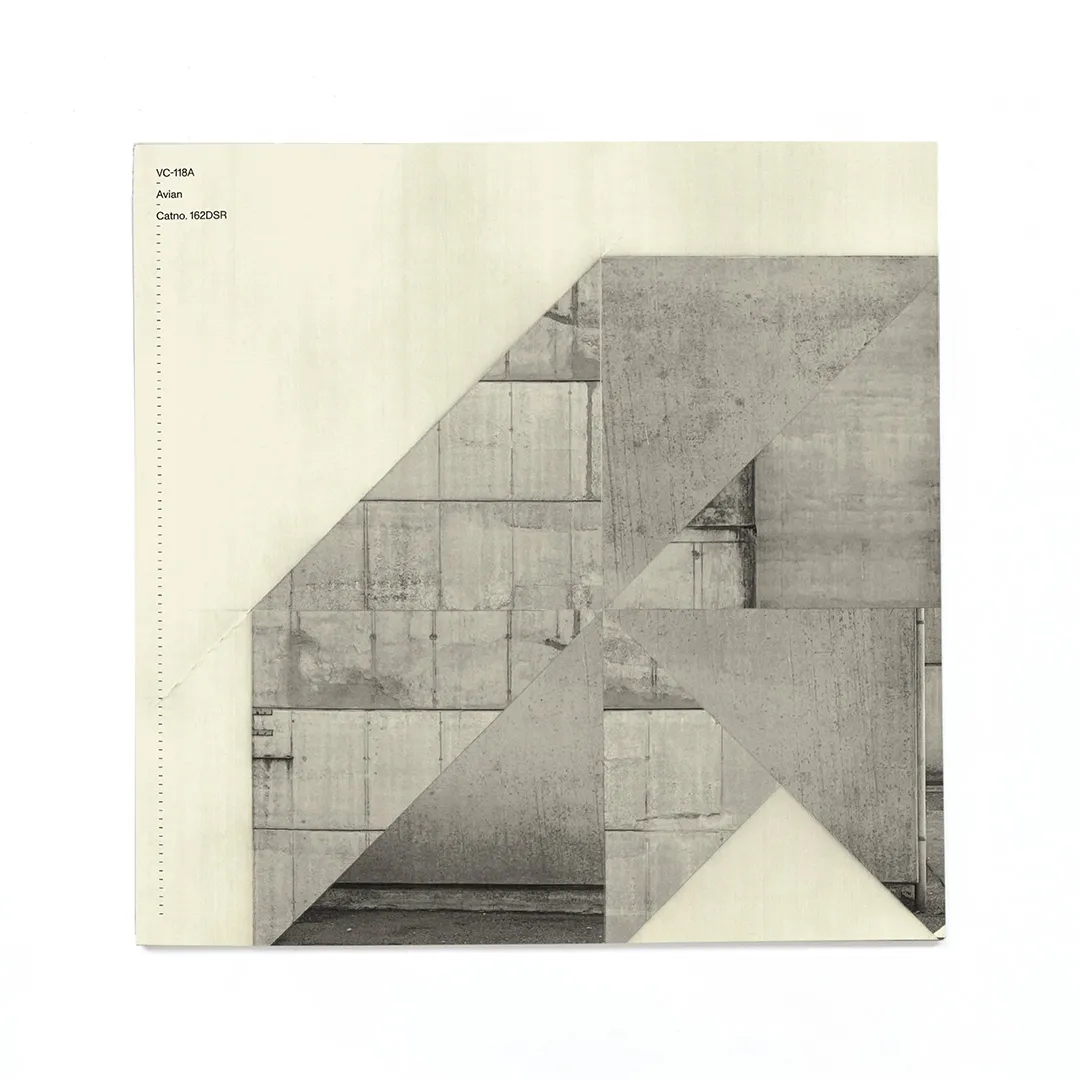

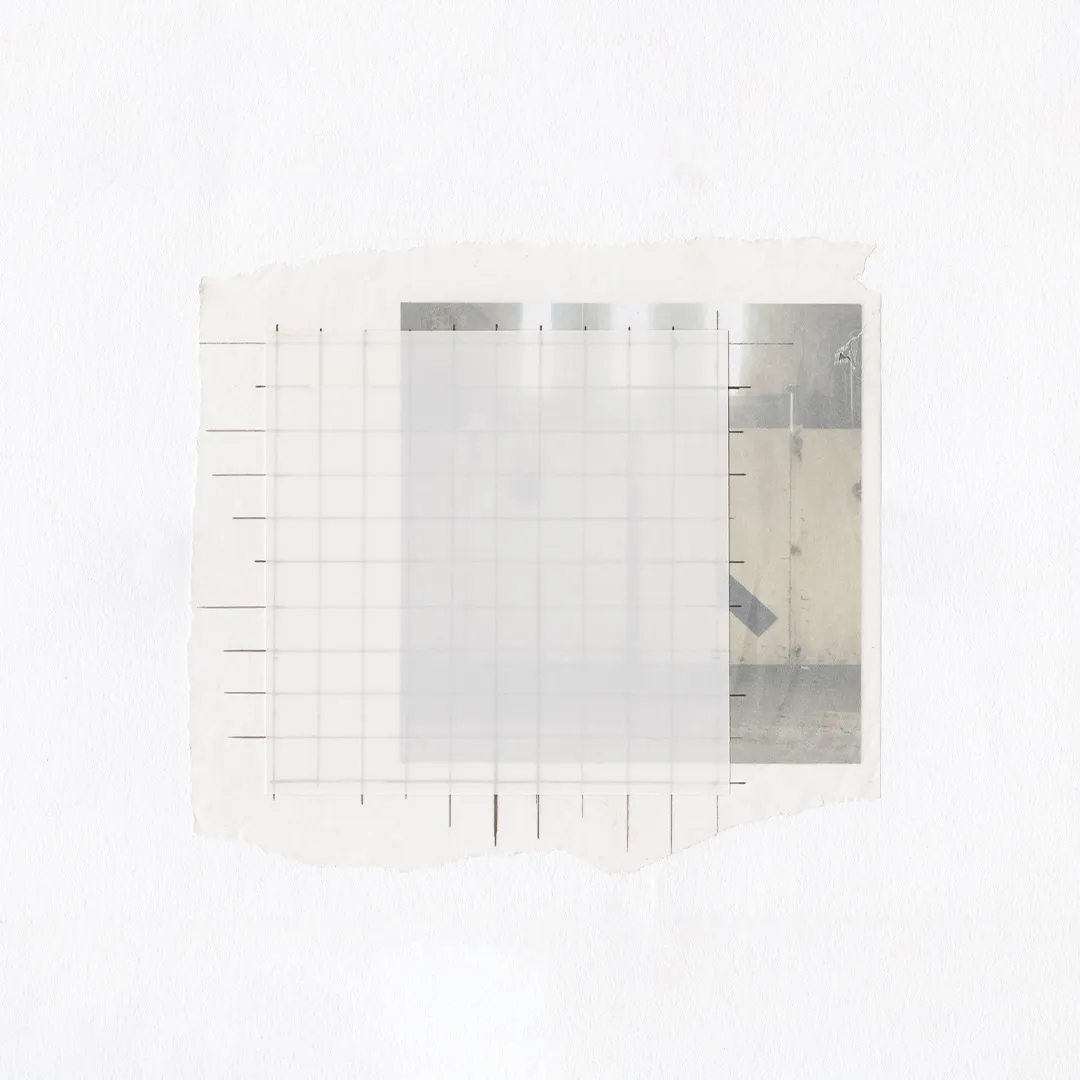

Next to De Stijl and the minimalists, Huigens has another grid inspiration, closer to home. His father, a garden and landscape architect, left a rich archive of research material, books, and transparent grid paper for his sketches. Erris brings out a couple of the grid papers, which also seem thoroughly examined by silverfish. He demonstrates how he layers grid paper with photographs of his paintings on factory walls – a technique he applies to the album cover of Xenia Reaper’s latest release on the techno label Delsin Records, which he designed together with designer Tijl Schneider.

These artworks are naturally a dialogue between the music and the cover art. ‘Sometimes, if a producer has a clear concept for an album or when it carries a very distinct atmosphere – for example, dark - I respond to that in my artwork with Tijl.’ Much like music, he samples pieces from his work and configures them for these album sleeves, in which he again plays with grid textures and geometrical grid particles.

‘In the end, it’s a constant play between order and breaking that order – a game between perfection and imperfection.’ All this has to do with Huigens’ state of mind: several times he mentions that, inside his head, it’s quite a chaotic place, with racing thoughts and a stream of observations. The order of the minimalist grid gives him control and peace – after which he ploughs through that order again: ‘By watching, observing, and returning.’

Beyond just music, the grid extends into the digital domain. The screen you’re currently reading this feature on is structured by a grid – the interface, the layout, and the logic itself follow the same principles of order and measurement that Huigens explores in paint and site-specific interventions. Within this framework, Erris collaborates with FORM, an independent research platform dedicated to contemporary art and AI-based curation, exploring how systematic structures can generate new visual experiences.

Here, the grid becomes both method and mindset: a way to organise, disrupt, and reconfigure not just physical forms but also digital and algorithmic processes. In this context, the same tension between order and chaos that drives Huigens’ painting is mirrored in AI-curated sequences, hybrid documentation, and the choreographed instability of digital images – proving that the grid is a binding force across disciplines, linking traditional craft, site-specific interventions, music, design, and the logic of digital creation.

It seems wherever we go, we interact with the grid. Sometimes as a subject of inquiry, other times as a tool for structure and order. From canvas and industrial walls to album art and digital interfaces, the grid is everywhere. Both aspects can live side by side, as Erris Huigens’ minimalist work proves – a system that binds traditional craft, music, design, and even AI-curated experiences, showing that order and creativity are never separate.

.webp)